Hawken’s Perspective: Overcoming a Fractured Femur with Duchenne

There’s plenty of times in life where plans fall apart. That’s especially the case if you have Duchenne muscular dystrophy like me. A building you were expecting to enter might have stairs instead of a ramp. A kidney stone, because of a sedentary lifestyle and increased medications, can pop up out of nowhere at the most inopportune time. With weakened bones, a simple fall while on vacation can turn into a fracture.

I experienced that aforementioned catastrophe while traveling to Miami for CureDuchenne’s Napa in Miami fundraising event. We had just gotten to the hotel on the Thursday before the event that weekend. I got up to go to the bathroom at 4:30 a.m. I usually walk to the toilet and do my business on my own. This night was no exception. But on the way back to bed, my third toe connected with a chair leg. The relatively small impact, combined with my already weakened muscles, was enough for me to lose my balance and my constant battle against gravity. I twisted to my left side before falling. The first thing to hit the hardwood floor was my left hip. My face also crashed into my travel wheelchair’s footrest, and it was a miracle I dodged any damage there. My hip was not so fortunate. Unbeknownst to me at the time, I had sustained a fracture close to where the femur locks into the hip socket.

My dad picked me up and carried me back to bed. It hurt a lot. I cried. The tears were more for the realization of what had just happened than the pain. But there was a lot of pain. We prayed for my left hip. It was in God’s hands now. We also iced my leg. This had happened before, it was just a bruise. The ice would help. Just go to sleep, it will be fine in the morning. That’s where my hopes were centered, but they came crashing down as I tried to stand and put weight on it.

My dad made the call: “We’re going to the emergency room.”

I didn’t want it to be true. It still meant that I had to get my pants and shoes on and get in the car. That was the worst part of the whole ordeal. A ghost stabbed a kitchen knife into my hip every time I moved from the bed to the wheelchair from the wheelchair to the car. But if my past experiences in the hospital said anything, it was that it’s better to be safe than sorry.

I was in no less pain lying in the hospital bed at Mount Sinai Medical Center in South Beach, Miami, but I felt safer knowing a doctor was close by. On the flip side, we were also away from my Duchenne specialists at home. It helped that my right wrist carried a Medical ID Bracelet. The metal inside of the plastic ring holds a QR code with my medical history, medications, and standards of care for Duchenne. The QR code also links to CureDuchenne’s emergency guidelines (CureDuchenne is not a medical provider; these guidelines are a point of reference).

The bracelet holds one of the most important details: I can’t under any circumstances take succinylcholine, or succs, for anesthesia. Succs can cause hyperkalemia (tightened potassium levels), which can lead to heart palpitations, shortness of breath, and vomiting. At worst, it can be fatal.

Also, the dreaded fat embolism. Some of the fat stored in a bone can block blood vessels and lead to serious symptoms such as a fast heartbeat, trouble breathing, and seizures. These can’t be prevented, only managed by emergency room staff. It’s important for doctors to be made aware because they can potentially overlook it, and it’s often diagnosed as pneumonia.

It’s worth noting here that you should update the information found in the Medical ID Bracelet with your most recent medications, address, and known allergies. Anything else can be added to the notes section on your profile page.

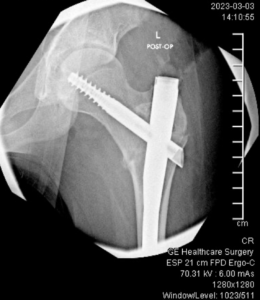

We instructed the ER doctor, Dr. Frost, to scan the QR code with his phone. It was new to him, but no less useful. It took the burden off my dad and I having to remember all the Duchenne care guidelines. Just show him the bracelet and let him read. Dr. Frost got the memo, assessed the situation, and devised a plan of attack. The first part of it was figuring out the damage. An X-ray tech eventually wheeled me out of the ER room to take photos of my hip. I was already bracing for that kitchen knife when they moved me to the X-ray table.

My body was screaming at me. Still, I made it back in one piece.

The first doctor arrived at the small, curtained off room. “You’ve fractured your femur, but it looks quite minor.” My dad and I released a small, hopeful sigh of relief. We looked at each other. Minor isn’t that bad, right?

Dr. Frost had a different opinion. It was a serious fracture. You’ll need surgery. A rod will be put in to help stabilize your femur. I put my hand up to my face. That was the last thing we wanted to hear. There’s a chance I’d never be able to walk again. My dad put it in simpler terms to the doctor. It turned out the operation was the best course of action, but we didn’t know it at the time.

For young people without Duchenne, a fracture isn’t as serious. They may be sent home and asked not to put weight on it for a few months. Maybe a doctor will wrap the leg in a cast. Give it time to heal.

That doesn’t work for me. I don’t have the strength to rely on one leg to move around. Crutches are out of the question. Even a walker is hard for me to use. If I don’t use that leg for months, it will start to atrophy. That happens fast in Duchenne. Walking would be out of the question. My bones, thanks to chronic corticosteroid use, are weaker. The support of a metal rod can help. I think it will make me stronger. I’m ready to reprise Arnold Schwarzenegger’s role as the Terminator.

I was scheduled for the rod placement surgery the next day. If you want to be official: intramedullary rodding of left subtrochanteric fracture.

After a long wait in the ER for a hospital room and talking up the manager of the ER about his upcoming plans at Coachella, hoping to move the process along, a transporter came in and wheeled me up to the fifth floor.

Laying in the hospital room bed dozing (I only slept two hours that night), I tried my best to gather information from my doctors, therapists, and trusted medical advisors. I called and emailed my primary neurologist at University of Massachusetts Medical School, Dr. Wong. She allayed my concerns, while also reminding me of a potential fat embolism. She spoke with the orthopedic surgeon and consulted with Dr. Whittles on the best course of action. Putting the rod in was the best option and is commonly done for other boys with Duchenne.

I did not have a pleasant night’s sleep in the hospital. But I was at least tired enough where I got some shuteye.

Around 10:00 the next morning, I was wheeled into the pre-op room. Surgeons with lime green scrubs scuttled across the polished white vinyl floor. A screen off to my right showed the operating room schedule. I was there for about two hours without any device to keep me occupied, so I observed the comings and goings of the nurses, doctors, and patients. I listened to conversations in Spanish and strained to see how much I understood.

My parents finally arrived. Guests aren’t typically allowed in the pre-op room, but it turns out my mom can be very convincing. Then Dr. Whittles, the orthopedic surgeon walked us through the procedure. He had never worked with a Duchenne patient before, so we went through the whole explanation that my bones are weaker, etc., etc. Dr. Whittles was honest with us about what he didn’t know, and we filled him in on the rest. We all appreciated his honesty, humbleness, and care. I could tell he was going to do the best he possibly could.

The last memory I have is one of the nurses injecting a liquid with a purplish hue into my IV, saying, “This is going to help relax you.”

I woke up and the first thing I did was thank God that I was alive and breathing. But I was also shaking like a jackhammer attacking a cement block. Having a rod jammed down the center of your femur does a number on your body. Apparently, my parents came up and talked to me for a bit. I don’t remember saying anything, but I know that I found my mom’s hand and squeezed it hard. She later told me that about made her heart burst. Waking up from anesthesia is like separating a dream from reality. What’s real and what isn’t blend together.

After what felt like an eternity, I was wheeled up again to my hospital room, where my dad and my roommate (bless his heart, he flew out from California to be with me) greeted me.

One of my dad’s salesmen and his friend who plays receiver for the Miami Dolphins brought me a smoothie, which will always go down as the best smoothie ever because I hadn’t eaten in a day, and it soothed my throat where a plastic tube had just been.

The pain finally got the best of me, and my visitors left me alone. I’m thankful that pain medication exists. Post-op, I took Toradol, an anti-inflammatory drug that NFL players use to compete through injury, and Tylenol. I opted against the morphine because I learned it could cause constipation, and I did not need or want that.

Between Friday, the day of my surgery, and Tuesday, the day I was released, I made sure to communicate my needs as best as I could. I had to guide the nurses through transferring me to the commode, rolling me in bed, and putting on my night splints. A physical therapist immediately wanted me to do strengthening exercises in my arms to help me stand. That wasn’t happening, I said. With Duchenne, we don’t do strengthening exercises. That does more damage.

On Saturday, I was able to put weight on my leg for the first time and stand for a few seconds. The therapists wheeled in a device that stood me up halfway. Knee guards in the front locked my legs and what I refer to as a “butt flap” kept my bottom from falling. From that position, I could stand erect for a moment and jumpstart the healing process with weightbearing. It was a miracle how fast I progressed from surgery to functional movement.

I gave what would have been my Napa in Miami speech from my hospital bed. I wanted to show people I was doing OK. I also wanted to show them why we need to cure this thing. My roommate filmed it with his fancy Canon 5D DSLR. I think it went over well. We raised more than $1.2 million that night to help fund a cure for Duchenne.

My day of freedom came quickly. If you’ve ever been in a hospital before it can be a blur. Food three times a day. Get up to poop once a day. Physical therapy torture. Sleep.

I’m thankful that I had no shortage of visitors, and my roommate could hang out with me for a few hours a day. We had a lot of deep conversations during that time. We prayed a lot. We also laughed a lot. It really is the best medicine.

I enjoyed a bit of the South Beach sun, pool, and ambiance before we flew back home. The flight was miserable. My leg was fine, but I didn’t have time to pee between connecting flights and couldn’t use the lavatory (I fractured my femur, remember). Alas, I made it back in one piece.

When I got home, I also consulted with Jennifer Wallace, a physical therapist working with CureDuchenne Cares. Incidentally enough, she and her counterpart Doug Levine had hosted a webinar last year about recovering ambulation (walking) after a lower extremity fracture. She sent me a few exercises that I could do to ensure that when I wasn’t walking, my muscles wouldn’t atrophy. That included sliding my knees up to a bent position, moving my leg side to side while laying down, and activating my quad muscles by pushing my knee down. The CureDuchenne PT team is truly world class.

I’m happy to report I’m taking a few steps on my own now and feel even closer to normal than I ever thought I could when I was laying there defeated in the hospital. It was a series of miracles: a skilled orthopedic surgeon with empathy, being close to friends and family, information specific to Duchenne was right on my wrist, and my personal care assistants who pushed me towards recovery. It was also staying calm in the face of adversity, learning from past experiences, and exuding a positive attitude despite it all.

Things happen outside our control. A lot more so with Duchenne. We are forced to survive and do the best with what we’ve got. I always remember that God is on my side no matter what. I’m confident where I’m going no matter what happens in this life. These are the things that keep me alive when it seems as though the world conspires to destroy me.

If I got through it, you can too. We have Duchenne together. We’ll get through it together. We’ll cure it together.